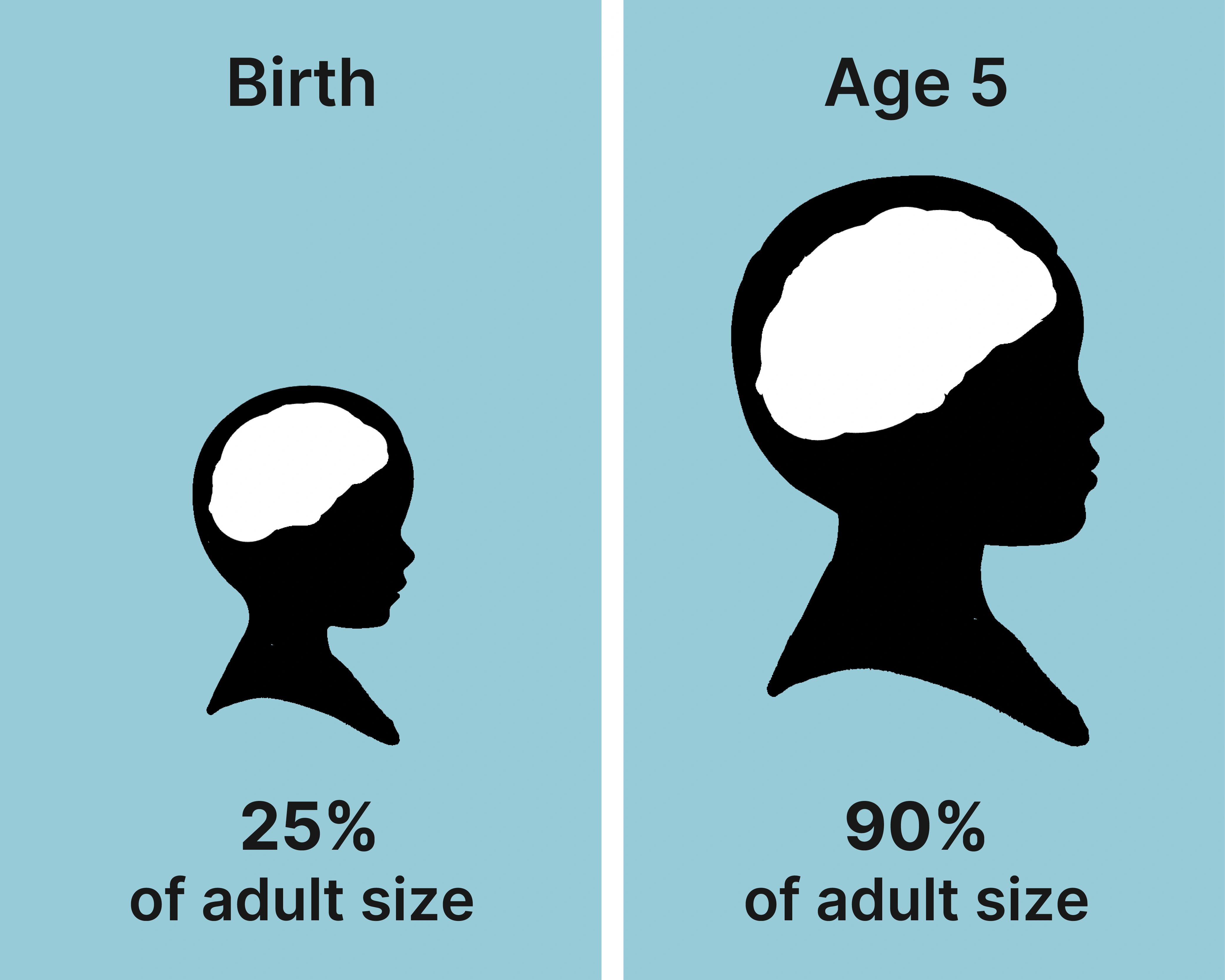

By the time a child learns to tie their shoes, their brain is almost fully grown.

Around 90% of brain growth occurs before a child starts kindergarten. Between the day a child is born and the time they turn five, brain size more than triples. This development enables children to learn at an incredibly rapid rate.

Newborn babies can only communicate verbally by crying and cannot recognize faces. Yet, a few years later, most children speak in complete sentences and understand abstract concepts like numbers and spatial directions.

Because these changes are common, it is easy to overlook how dramatic they are. The amount of learning that can occur in early childhood is nothing short of miraculous.

Unfortunately, some families lack the resources to help children take advantage of this stage of learning. Studies show that toddlers in low-income households have vocabularies 30 percent smaller than those of their higher-income peers. Many children are already a year behind in language development at the start of kindergarten.

We saw evidence of this in recent work with a large U.S. school district. Our analysis showed that around 50% of children from low-income families were not ready for kindergarten when they started elementary school.

Even worse, those who started behind tended to stay behind. We found that most of the low-income children who failed to read at a basic level in third grade were students who arrived at kindergarten unprepared.

Gaps like these carry lifelong consequences. Academic difficulties during elementary school are linked to higher dropout rates, lower adult earnings, and an increased risk of involvement in violence.

Why do so many children fall behind? We have identified three ways communities fail to meet children’s needs in early childhood.

Missing programs. Pre-K instruction and Head Start are not enough on their own. Communities should offer each child a minimum of six distinct services during this critical life stage.

Unfocused enrollment. The children most in need of early childhood support are often the last to enroll. Many communities do not even have systems in place to know how many of the highest-need young children participate in local services.

Poor implementation. Badly run programs can be worse than no program at all. Recent research found that children placed in an underfunded pre-K program in Tennessee had lower reading performance than those who received no instruction at all.

Communities that fix these problems are likely to see massive rewards. The gains children make during this stage of life can last for decades. Analyses indicate that every dollar invested in effective early childhood programs generates between two and nine dollars in long-term benefits.